Wind in the willows

In which I am captured by country animals and a pagan god

22 August 2022

Kenneth Grahame's Wind In The Willows was published in 1908 when automobiles and steam trains hadn’t overrun rural England quite yet. The rivers run clean, freight plods along canals at the speed of a weary horse and motor vehicles are still a stirring novelty. It’s still low rpm’s in the industrial revolution. No wars yet but there are rumblings.

Grahame’s descriptions of his countryside are beautifully evocative - his streams, feeding the upper reaches of the Thames, chatter, murmur and sparkle, new days emerge from early morning fogs that fade like a dream, we’re invited into the comfortable snugness of a warm burrow and we hear and feel the long deep silence of a snowy wood in winter.

This idyllic countryside is home for the principal characters; the badger, mole, rat, toad, otter and all the other talking creatures such as stoats and weasels (but oddly not horses or pigs which the other animals ride and eat).

The talking creatures live alongside humans - policemen, train drivers, judges, washerwomen and so on - but, really most of the animals are just people too. Most are jolly good chaps. Very well spoken, well-off chaps they are too. Those sly stoats and weasels though, not the right sort at all.

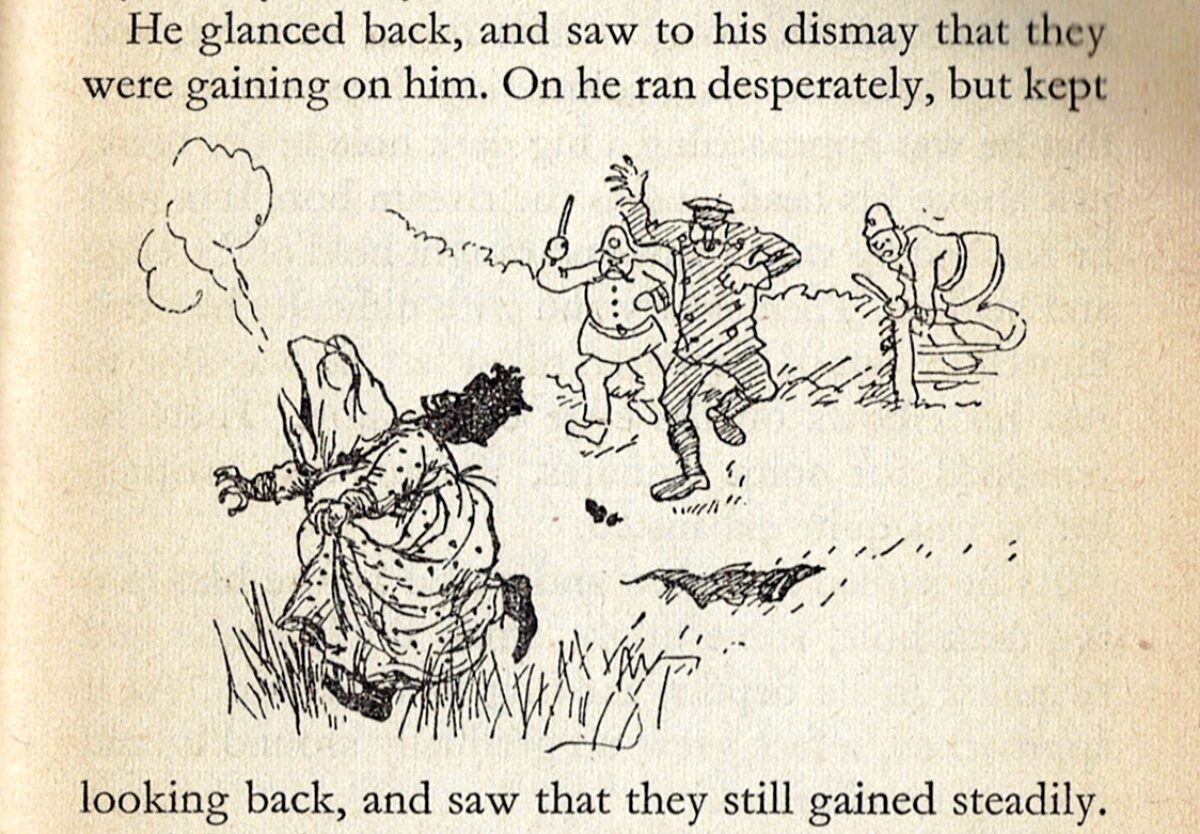

After Mole meets Rat, adventures ensue. A motorcar is stolen, a train hijacked, a house invaded, someone goes to prison. It’s quite exciting in its way, much like a thrilling tale for children with lots of pace but not too much jeopardy.

Wind In The Willows was written in a sense for one child. Grahame’s tales of Toad, Rat, Mole and Badger started as bedtime stories and letters for an audience of one; Grahame’s son, Alastair.

But Wind In The Willows was written for all readers some of whom might just happen to be children at the time of reading. Grahame’s prose never talks down to his younger reader, he tells a child’s tale as if for adults. The reader has to pay attention to the humble commas because that’s where the delightful rhythm and prosody of his writing breathes life into his characters.

The adventures in Grahame’s idealized notions of a verdant and bucolic England are innocent of guile or malign intent so it’s all very rousing and jolly and delightfully angst-free but then, all of a sudden, with a turn of the page, you’re deeply and richly immersed in the realm of pagan animism.

This is the chapter that transports the reader’s imagination far, far from the tepid, milky teachings of the Church of England.

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.

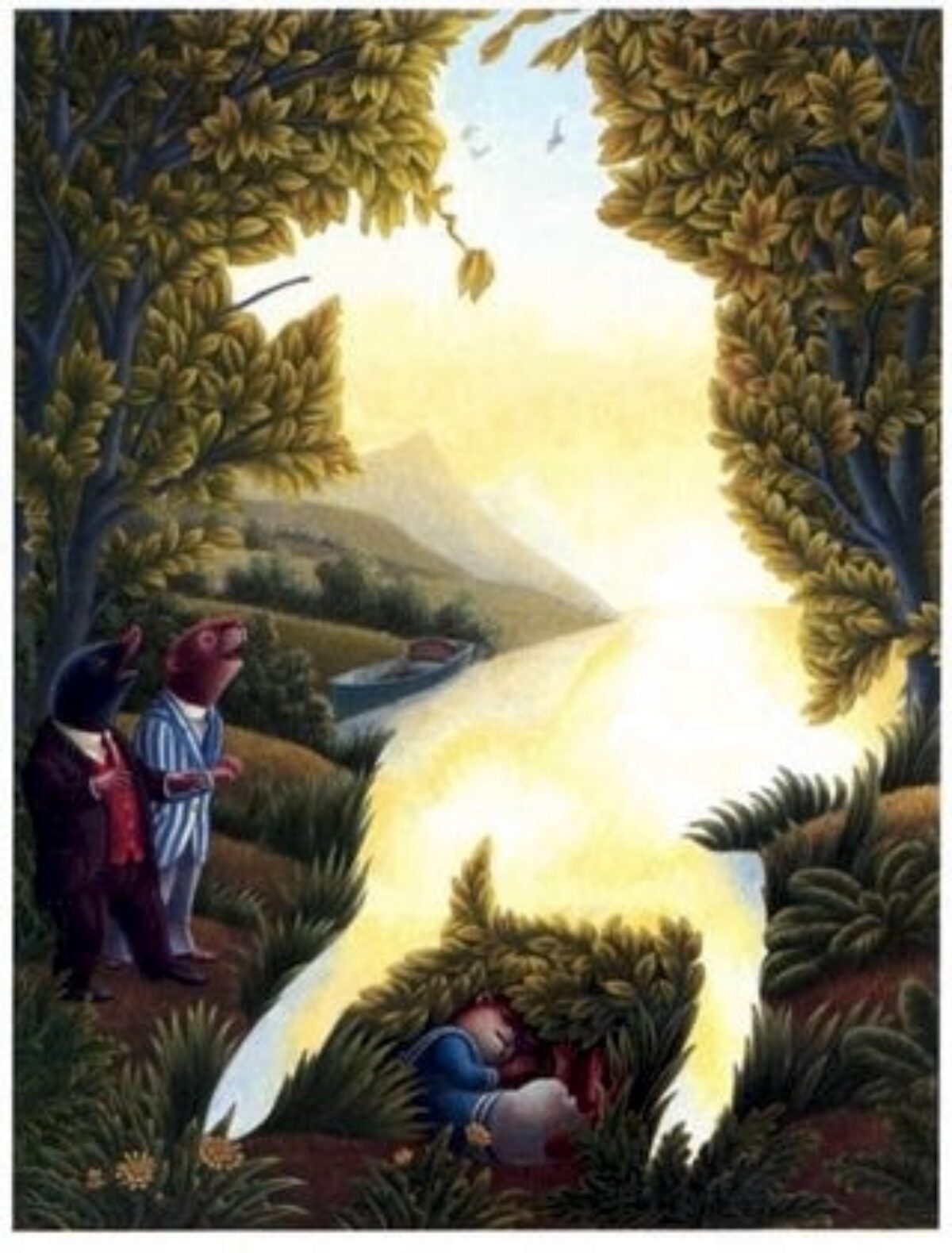

This chapter leads Rat and Mole into another less domesticated, wilder England, ancient, primal and elementary.

Night has fallen and a young otter, Little Portly, is still lost in the Wild Woods. Rat and Mole take the rowing boat and go searching.

Here’s the first mention of the wind but it isn’t amongst the willows ‘a light breeze sprang up and set the reeds and bulrushes rustling’.

But Rat hears something else on the wind and is entranced. ‘I hear nothing myself,’ says Mole, ‘but the wind playing in the reeds and rushes and osiers.’

But then the intoxicating panpipe melody that enraptured Rat imposes its will on Mole.

Commanded by the music, they follow the sound of panpipes and Mole rows them to what Rat calls a ‘holy place’, a small island by a weir, just as dawn is breaking.

Rat and Mole tie off their boat and push through the undergrowth. Emerging into a clearing they find the young otter asleep and unhurt lying at the hoofed feet of the great god Pan.

In the numinous presence of Pan, Ratty and Mole have a transcendental vision and a very lovely vision it is too.

Grahame illuminates a vision of vital natural forces ‘the Friend and Helper’ that pre-dates Christianity and this episode of pagan animism initially seems so at odds with the Church of England wholesomeness that permeates his other chapters.

Grahame’s nostalgia for pre-Christian deities though sits comfortably with another of Grahame’s themes - a yearning for a wholesome life untroubled by doubts or yearnings for far horizons and unclouded with fears, protected and cared for with no thought given to the modern world barreling towards him.

Grahame’s dim view of the modern world is revealed in chapter 1 after Mole asks what is beyond the Wild Wood Rat has just introduced him to.